Antonio Giustozzi with Niamatullah Ibrahimi

Published by the

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation UnitThe authors provide an accessible analysis of the social and political factors underlying the long conflict. The purpose is to “bring together the existing literature, review it, and start a more rigorous discussion of what has been driving anti-government mobilisation in Afghanistan for over 30 years. The paper has therefore been designed to highlight existing gaps in the literature, map future research opportunities and needs, and provide an initial, although not conclusive, brief on what existing evidence suggests are the main drivers of mobilisation in the current situation.”

The key point.

“The current, post-2001 armed confrontation can be seen as the third phase of a conflagration that started in 1978. From a political analysis perspective, minimising the differences between the different phases of the conflict might seem debatable. However, when the underlying social, cultural, and political factors are analyzed, it becomes clear that the ongoing phase of the conflict cannot be understood without looking at the previous phases as well (which is not to say that the violent, recent past is a sufficient cause of the current conflict). Prolonged conflict reshapes society, often changing the reasons why a conflict is fought. The original destabilisation of the country in the 1970s created an environment in which various sectors of the population were mobilised by different political movements, each carrying out a revolution (or trying to) against its predecessors and subject to external interference. It also changed Afghan society to a fair extent and even created two new social classes with a heightened self-consciousness of their political role: the clergy and a class of military professionals (the “commanders” as they are known in Afghanistan).”

Executive Summary

The literature concerning the last 30 years of war in Afghanistan has over the last few years reached such a critical mass that it is now possible to identify structural factors in Afghan history that contributed to the various conflicts and have been its signal feature from 1978 onward. The state-building model borrowed from the neighbouring British and Tsarist empires in the late 19th century contained the seeds of later trouble, chiefly in the form of rural-urban friction that gained substantial force with the spread of modernity to rural Afghanistan starting in the 1950s. Following the Khalqi regime’s all-out assault on rural conservatism in 1978-79, this friction ignited into large-scale collective action by a variety of localised opposition groups, including political organisations, clerical networks, and Pakistani military intelligence, as well as the intelligence services of several other countries.

During the 1980s, Soviet heavy-handedness, combined with the local dynamics of violence and massive external support, intensified and entrenched the existing conflict. New social groups emerged with a vested interest in prolonging the conflict, while existing social groups were transformed by it. Communities everywhere armed themselves to protect against roaming bandits and rogue insurgents, eventually dismantling the monopolisation of violence that Amir Abdur Rahman had started to marshal from 1880 onward.

In 1992, on the eve of civil war, the national army and police, as well as the security services, were disbanded. This was a complex process, featuring factional infighting and the desire of the new mujahiddin elite to eliminate an alternative and potentially rival source of power. Armed insurgent groups eventually became semi-regular or irregular militias with little discipline and weak command and control from the political leadership. As a result, Afghanistan reverted to the pre-Abdur Rahman state of rival and semi-autonomous strongmen, with the central government having to negotiate for their allegiance.

Explanations of the Taliban’s rise usually refer to the disorder and chaos that characterized this situation as it existed in Afghanistan during 1992-94; however, the biggest challenge now is to understand how such an example of collective action could take place in a fragmented political and social context.

In 2001, the new interim government took power and inherited a heavily compromised situation. Rather than mobilising scarce human resources and reactivating as much of the state administration as possible, the government instead emphasized patronage distribution, in the process surrendering virtually all levers of central control to strongmen and warlords associated with the victorious anti-Taliban coalition. This combined with other factors to radically undercut governance, which undermined the state’s legitimacy and pushed some communities toward revolt.

The predominant social, cultural, and economic trends of the post-2001 period abetted the spread of the Taliban’s recruitment base by deepening the rural-urban divide mentioned above. The concentration of economic growth in the cities, the arrival of mass media typically rather disrespectful of the villages’ predominantly conservative social mores, and the affirmation of capitalist attitudes at the expense of established redistributionist attitudes among the wealthy classes, all contributed to the population’s polarisation. Massive levels of expenditure in Afghanistan also triggered an inflationary process, which badly harmed all those who were not direct financial beneficiaries of the intervention.

The clergy, having much to lose in the new political set-up, gradually remobilised as an opposition force. Its general expansion and prior military experience, along with the fact that many of its members had been part of a single political organisation (Harakat-i- Enqelab) during the 1980s, had all contributed to the re-emergence of a militant clerical movement in 1994, as did the jihadist indoctrination of new generations of clerics. By steadily co-opting more and more local clerical networks, the Taliban not only expanded, albeit temporarily, but also socialised newcomers into the movement, thereby creating a relatively strong sense of identity. The idea of clerical rule seems only gradually to have gained ground within the Taliban, but by 2001 it was entrenched within their ranks.

The Taliban are often depicted as relying on poverty and social marginality as spurs to the recruitment of village youth, although there is little actual evidence of that. Whatever the cause of many young Afghans joining the insurgency, mercenary motivations seem to dissipate once the Taliban have a chance to socialise and indoctrinate their new members. The behaviour of the Taliban in the battlefield suggests that mercenary aims are not a major, long-term motivating factor.

The Taliban have also been seen as a Pashtun revanchist movement, aiming to redress the imbalance that emerged in 2001 when mostly non-Pashtuns seized control of the state apparatus. In fact, there is growing evidence of the Taliban recruiting from the ethnic minorities as much as possible. While it is possible that some Taliban supporters might after 2001 have seen them as a source of Pashtun empowerment, there is little or no evidence that such considerations have played an important role in recruitment.

By contrast, there is substantial evidence that the Taliban have exploited conflicts among communities to establish their influence, if not necessarily to recruit individuals to their cause. In a number of occasions, the Taliban have also succeeded in mobilising disgruntled communities on their side, encouraging them to fight against government and foreign troops. Such community mobilisation was mostly relatively short-lived, as the communities were extremely vulnerable to the reaction of the Afghan state and the Western armies and suffered heavily in the fighting; by 2011, such mobilisation appeared to have declined.

Much has been said on the role of opium in fuelling the conflicts over the years. While it is evident that insurgents tax the drugs trade, their involvement in it is likely to have been overstated. In reality, the Taliban do not appear to attribute much importance to the drug taxes raised in southern Afghanistan and were in early 2011 shifting their military effort to other areas of the country. While narcotics revenue likely represents a solid majority of the Taliban’s own tax revenue, external support from Pakistani and Iranian sources is reportedly a significantly larger portion of their overall revenue. Similarly, since the Taliban tax any economic activity, including aid contracts and private security companies, development aid theoretically fuels the conflict as much as the narcotics trade does.

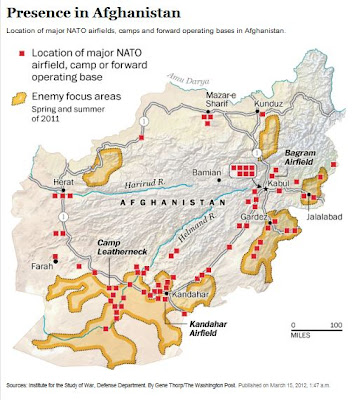

The intensification of the international military presence from 2006 onward, meant to contain the insurgency, has had the opposite effect, with greater numbers of troops eventually presiding over an acceleration of the insurgency’s expansion. In part this was due to regional powers increasing their support as a particular reaction to the growing American presence. The acceleration of the insurgency’s spread was also the result of local reactions to the presence of foreign troops.

In order to fully explain the post-2001 insurgency, a unifying factor is needed, a “driver of drivers.” The Taliban have been able to link together and integrate various causes and groups, capturing their energy and rage and directing it toward the strategic aim of expelling foreigners from the country and imposing a new political settlement. In their use of xenophobic and occasionally nationalistic recruitment arguments, the Taliban, aware of the difficulty of fully integrating communities under their own leadership into the movement, have privileged the role of individuals.

There are many weaknesses and gaps in our knowledge that should be addressed in order to confirm or reject some of the hypotheses formulated here. In particular, the Taliban’s organisational system is still poorly understood, as is their system of socialisation. Social and political dynamics such as the urban-rural divide and the impact of cash inflows after 2001 are also poorly understood. How much of the pre-war social organisation is left intact or at least functional is also far from clear. Future research would certainly benefit from a comprehensive mapping exercise.